The Saskatchewan Science Centre Online! Check out our hilarious and educational web series “SSCTV”, find downloadable resources, explore other cool science links, and tune into the live BUBOCam!

Elements R Us With Tommy Tungsten - Fluorine

In this video, Tommy Tungsten tells us all about Fluorine.

From CFCs to whiter teeth, come on down to Elements 'R US for all your Fluorine needs!

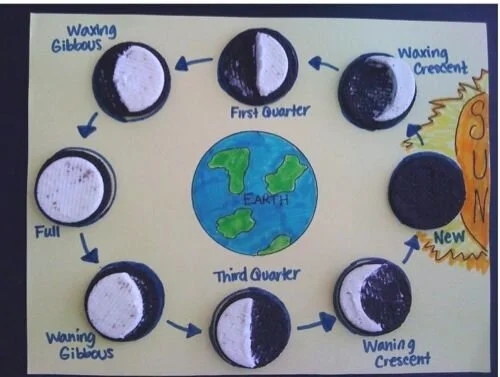

Phases of the Moon

The moon isn’t just a beautiful aspect of our night sky, but one of nature’s timekeepers! The moon is on a 28-day cycle, called the moon cycle, and that’s exactly what we’ll be exploring today.

The moon isn’t just a beautiful aspect of our night sky, but one of nature’s timekeepers! The moon is on a 28-day cycle, called the moon cycle, and that’s exactly what we’ll be exploring in this video.

Loving this content? Make a donation to the Saskatchewan Science Centre!

#letssciencethis #SaskScienceCentre #AtHomeWithCASC #ScienceChampions #ScienceAtHome #realsciencerealfun

Tour of the Saskatchewan Burrowing Owl Interpretive Centre

Tour of the Saskatchewan Burrowing Owl Interpretive Centre

Welcome to the fascinating world of owls. We are taking you on a tour of the Saskatchewan Burrowing Owl Interpretive Centre. You’ll get to know lots of cool facts about burrowing owls and how they are doing in Saskatchewan!

What Is A Virus?

Viruses are the most abundant pathogen on Earth. Viruses are microscopic parasites, generally much smaller than bacteria. They lack the capacity to thrive and reproduce outside of a host body such as bacteria, animals, or plants. Each viral particle, or virion, consists of a single nucleic acid - RNA or DNA - surrounded by a protein coat. The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms to more complex structures.

What is a virus?

A pathogen is a biological agent that causes disease or illness in a host. Viruses are the most abundant pathogen on Earth. Viruses are microscopic parasites, generally much smaller than bacteria. They lack the capacity to thrive and reproduce outside of a host body such as bacteria, animals, or plants.

Each viral particle, or virion, consists of a single nucleic acid - RNA or DNA - surrounded by a protein coat.

The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms to more complex structures. Most virus species have virions too small to be seen with an optical microscope as they are one hundredth the size of most bacteria.

Outside of a cell, a viral particle is inert. A virus is capable of replication only within the living cells of a host. Once a host cell is infected, the host is forced to rapidly reproduce thousands of identical copies of the virus, which are then able to spread and infect other cells.

Is a virus alive?

Viruses are not capable of reproducing on their own; they can only reproduce within the living cells of a host organism. While many people debate the definition of what makes something alive, the ability to reproduce independently is often considered to be one of the seven characteristics of living things. Viruses are genetic material (DNA or RNA) but are not generally considered to be alive.

Where are viruses found?

Wherever there is life, there are viruses. They are found in soil, the air that we breathe, and oceans. They are a part of almost every ecosystem on Earth. They even live in extreme environments such as hot springs, deep ocean thermal vents, and Antarctic ice.

Are all viruses bad?

Not all viruses are harmful. Viruses play a critical part in our ecosystem and are helpful in sustaining life on Earth. For example, viruses help the microbes in the ocean produce oxygen. The oxygen that these microbes produce accounts for nearly half of the oxygen on the planet. A class of viruses known as bacteriophages can even kill a spectrum of harmful bacteria, providing protection to humans.

How do viruses spread?

Viruses spread in many ways.

One transmission pathway is through disease-bearing organisms known as vectors: for example, viruses are often transmitted from plant to plant by insects that feed on plant sap, such as aphids; and viruses in animals can be carried by blood-sucking insects, such as mosquitos.

Infection can also occur via the exchange of blood and bodily fluids, via contaminated food or water, respiration of viruses contained in aerosols, and fecal matter. Some viruses can live on surfaces outside the human body and can be acquired through cross-contamination due to unsafe handling practices.

Some viruses are spread easier than others. The term R0 (pronounced “R naught”) is used to describe the transmissibility of a disease. Each person infected with a disease with an R0 of 5 would, on average, infect 5 otherwise healthy people. The R0 of the 1918 Swine flu (Spanish Flu) was estimated to be between 1.4 and 2.8.

What infections do viruses cause?

Viruses infect all living organisms: plants, animals (including humans), and bacteria. Only a tiny fraction of the viruses that surround us actually pose any threat to human life or health. Some well-known human diseases caused by viruses include influenza, chickenpox, HIV, Ebola, cold sores, and the common cold.

The term “Virulence” is defined as the ability of a microbe to cause disease or damage in a host. In other words, the more virulent a virus is, the more dangerous it is to its host.

How does the human body fight against viruses?

Viruses make us sick by killing cells or disrupting cell function.

Our bodies seek to identify infections in several ways, and once identified will try to fight the infection. This fight, known as the immune response, includes the secretion of a chemical called interferon (which blocks viruses from reproducing), or the production of antibodies, and more.

In response to an infection, your immune system springs into action to destroy the disease. Many of the symptoms we feel when sick - fever, malaise, rash, headache - are a result of our own immune system trying to protect us.

Drugs prescribed by a doctor can also help your body to fight infections. People will often receive a prescription for an antibiotic such as Amoxicillin or Azithromycin as a treatment for a disease caused by a bacteria. However, antibiotics don’t work for infections caused by a virus.

Protecting yourself from disease

• Practice good hygiene: wash your hands thoroughly or use hand sanitizers

• Ensure that your food and drinks are safe to consume and hygienically prepared

• Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue when you sneeze or cough

• Practice safe sex and get tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases

• Use insect repellents to avoid bug bites and limit outdoor activity during peak mosquito hours of early morning and evening

• Stay clear of wild animals. Many wild animals, including raccoons, skunks, foxes, and coyotes, can spread rabies to humans by biting. Keep your pets away from wild animals as well, and make sure their vaccinations are up to date

• Get vaccinated to protect yourself and others

• Take travel precautions: follow the guidance of the World Health Organization and Government of Canada when travelling and avoid travelling to places where travel is not recommended or where there are Travel Health Notices. Work with your doctor to get additional immunizations or travel medicine as recommended.

How to protect society from disease

The velocity of the spread of disease correlates with a number of factors: human population density and sanitation being two of the most significant. There is evidence that many highly lethal viruses lie in biotic reservoirs in remote areas, and epidemics are sometimes triggered when humans encroach on natural areas that may have been isolated for long time frames; this theory has been suggested for many dangerous diseases including Ebola, HIV, and COVID-19.

Herd Immunity

Herd immunity is a term used to describe what happens when a large portion of a community has become immune to a disease. When enough people in a community have immunity to a disease, it makes the transmission of the disease very unlikely. The percentage of a population that must be immune to achieve herd immunity is called a “threshold proportion.” This percentage depends on how contagious the disease is - the R0. For some very contagious diseases, such as measles, this threshold can be as high as 94% of the population. To achieved herd immunity, enough people need to receive a vaccine for a disease or suffer from and survive a disease to build natural immunity.

Resources for Additional Reading

Viruses:

Infections:

Did you find this helpful? Consider making a donation to the Saskatchewan Science Centre!

What Is SARS-CoV-2?

In the first post of our Understanding COVID-19 series, we discussed what a virus was and whether they were alive. In this post, we’re going to discuss the specifics of SARS-CoV-2, which is the name of the virus that causes the disease named COVID-19.

What Is SARS-CoV-2?

In the first post of our Understanding COVID-19 series, we discussed what a virus was and whether they were alive. In this post, we’re going to discuss the specifics of SARS-CoV-2, which is the name of the virus that causes the disease named COVID-19.

The ‘Coronavirus’

Viruses are distinguished by their shape. When seen with a microscope, coronaviruses have a structure of proteins around them that are similar to the corona of the sun, which looks similar to a crown. The Latin word for crown is corona, hence coronavirus.

For many months now we have been interfacing with what is commonly referred to as “The Coronavirus”. Using the name “coronavirus” to describe the actual disease affecting so many people during this global pandemic is incorrect. This is because there are many known types of coronaviruses that have been discovered since the 1960s; some are able to infect humans and some can infect or be hosted by other mammals or birds. In fact, according to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, there are at least seven known types of coronavirus existing today that can infect humans. These are:

Types of Coronaviruses Known To Infect Humans

“Coronaviruses, a large family of single-stranded RNA viruses, can infect animals and also humans, causing respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and neurologic diseases.” The most common coronaviruses to infect humans are the alpha and beta coronaviruses which generally induce diseases such as the common cold and are very easy for doctors to treat. Because of this, research into coronaviruses was not a scientific focus until the discovery of the SARS-CoV-1 coronavirus. SARS-CoV-1 is the virus responsible for the SARS disease epidemic which affected 26 countries in 2003. According to the American Society for Microbiology, “Before the SARS epidemic in 2003, there were only 19 known coronaviruses, including 2 human, 13 mammalian, and 4 avian coronaviruses. After the SARS epidemic, more than 20 additional novel coronaviruses have been described with complete genome sequences.”

The Discovery of SARS-CoV-2

In December of 2019 Chinese health authorities reported clusters of patients with symptoms similar to pneumonia. Epidemiologists, scientists that study the systematic and data-driven patterns of distribution and determinants of health-related events, traced the origin of the symptoms to a seafood and live animal market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China.

After the SARS outbreak in 2003, epidemiologists established surveillance mechanisms to quickly identify potential new pathogens that might become a global health concern. These mechanisms identified the pathogen in the Chinese patients as sharing genetic similarities to SARS-CoV-1, and named this novel pathogen 2019nCoV. By January 2020, the World Health Organization expressed the resulting disease a public health emergency of international concern. “ICTV announced “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)” as the name of the new virus on 11 February 2020. This name was chosen because the virus is genetically related to the coronavirus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. While related, the two viruses are different.”

The WHO announced “COVID-19” as the name of this new disease on 11 February 2020, following guidelines previously developed with the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a new and previously unknown virus our knowledge of how it is transmitted, reproduces, and the resulting effects of the virus continues to evolve.

Understanding the Names: SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19

To better understand how scientists name different types of coronaviruses and diseases, let’s break it down. SARS stands for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. CoV stands for coronavirus. The number 1 in SARS-CoV-1 represents the first coronavirus discovered that caused Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. The coronavirus responsible for causing the COVID-19 disease pandemic has been named SARS-CoV-2. “This name was chosen because the virus is genetically related to the coronavirus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003.” In the early days of the pandemic, this virus was called 2019nCoV.

The name of the disease which is caused by SARS-CoV-2 - COVID-19 - can also be broken down to be better understood. The CO stands for Corona, the VI stands for Virus, the D stands for Disease, and 19 is the year the disease was first discovered. The term “novel” has also been used in association with SARS-CoV-2. The novel, in this case, is used to implicate SARS-CoV-2 as newly discovered. The N in 2019nCov was used to note that this was a novel virus.

“It is important to understand that when people or media outlets loosely use the word “coronavirus” to describe the current pandemic, they really are referring to only one of many types of coronaviruses that can infect humans: SARS-CoV-2. This virus infects people and causes the COVID-19 disease.”

The Link Between SARS-CoV-2 and Habitat Destruction

Zoonotic diseases, or diseases transmitted from animals to humans through bites, scratches, or ingestion, are not new. The bacteria responsible for the black death was transmitted to humans through flea bites, tuberculosis originated in cows and transferred to humans through consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, or by being close to an infected animal, malaria continues to be transmitted by mosquitoes, and Lyme disease is transmitted by ticks. In fact, “Six out of every 10 infectious diseases in people are zoonotic, according to Dr. Roland Kays, a Research Professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at NC State’s College of Natural Resources.”

The leading theory on the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 (but which has not yet been definitively proven) is that a virus that shares 96% of its genome sequencing with the SARS-CoV-2 was living dormant long ago in a horseshoe bat, or possibly a pangolin, was then transmitted to an intermediate host such as the meats found at the seafood market where the virus mutated, and then, was transmitted to humans. Once the SARS-CoV-2 virus took root in humans it spread and continues to spread across the globe at an alarming and exponential rate. The moment when a zoonotic disease mutates and transfers from animal to human is called a spillover event. “Wet markets make a perfect storm for cross-species transmission of pathogens,” says Thomas Gillespie, disease ecologist. “Whenever you have novel interactions with a range of species in one place, whether that is in a natural environment like a forest or a wet market, you can have a spillover event.”

It’s not fair to blame bats for COVID-19. What we need to understand about zoonotic diseases is that it is not just one type of animal that can carry viruses that could be dangerous to humans. There are countless viruses in a wide variety of animal or bird hosts that could potentially infect humans.

Habitat destruction, including deforestation and agricultural development on wildland, is increasingly forcing disease-carrying wild animals closer to humans, allowing new strains of infectious diseases to thrive and spill over into our communities.

“We invade tropical forests and other wild landscapes, which harbor so many species of animals and plants—and within those creatures, so many unknown viruses,” David Quammen, author of Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Pandemic, “We cut the trees; we kill the animals or cage them and send them to markets. We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it.”

This infers that if we do not start valuing and protecting natural habitats and the biodiversity of this planet, pandemics will likely become a more frequent occurrence.

How SARS-CoV-2 Spreads?

The current understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 (and accordingly, COVID-19) spreads is described on the Government of Canada website:

“SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, spreads from an infected person to others through respiratory droplets and aerosols created when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, shouts, or talks. The droplets vary in size from large droplets that fall to the ground rapidly (within seconds or minutes) near the infected person, to smaller droplets, sometimes called aerosols, which linger in the air under some circumstances.

The relative infectiousness of droplets of different sizes is not clear. Infectious droplets or aerosols may come into direct contact with the mucous membranes of another person's nose, mouth or eyes, or they may be inhaled into their nose, mouth, airways and lungs. The virus may also spread when a person touches another person (i.e., a handshake) or a surface or an object (also referred to as a fomite) that has the virus on it, and then touches their mouth, nose or eyes with unwashed hands.”

Other mammals, such as dogs and cats, can also become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, though they are considered a low risk to people. Other wild animals, such as minks and ferrets can also become infected. Some scientists are also concerned about the infection risk to endangered marine mammals through contaminated sewage or wastewater.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is extremely contagious, and preventing the spread of the virus is of the utmost importance. Simple measures, such as proper handwashing, wearing masks, social distancing, and regular cleaning and disinfecting surfaces are our best defences against becoming sick or transmitting the virus to others.

SARS-CoV-2 Variants

What are variants of a virus?

Viruses have the innate ability to multiply by creating copies of themselves when they are in a host. By creating abundant copies of its genome, the virus ensures its survival and thus continues to infect new hosts. During this reproduction process, some of the copies are not exactly the same as the original virus which makes a new variant of this virus.

Dr. Kara Loose, in her interview with the Science Centre, describes this with an analogy to writing. When we are trying to write (or copy) a text quickly, we make mistakes. Similarly, when a virus is trying to quickly multiply, it sometimes makes mistakes and does not create the exact same copy as the original virus. Sometimes these variations result in making the virus stronger, for example, by making it easier to spread. In other instances, these variants may include changes that make the virus weaker or unable to reproduce further.

How SARS–CoV-2 Variants Contribute to the Current Global Pandemic?

As the SARS-CoV-2 virus went on spreading across the Globe, it created multiple variants of the original virus.

Due to the rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 Pandemic, we recommend the following regularly updated resources to learn about SARS-CoV-2 variants:

WHO - https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

Did you find this helpful? Consider making a donation to the Saskatchewan Science Centre!